Bhutanese don’t have family names. They can have one, two, three or more names. Names are chosen by the astrologist consulted by the parents after birth, although some families will consult multiple astrologists and choose names from among several. Anyway, I am Dr. Steve here in Bhutan, often Sir, at times Uncle. I enjoy being Dr. Steve. Sir is a bit harder to get used to, especially in the third person (Would sir like to sit here?) Being called Uncle by an eleven-year-old girl, correcting me as I start around a chorten in the wrong direction, is actually kind of fun.

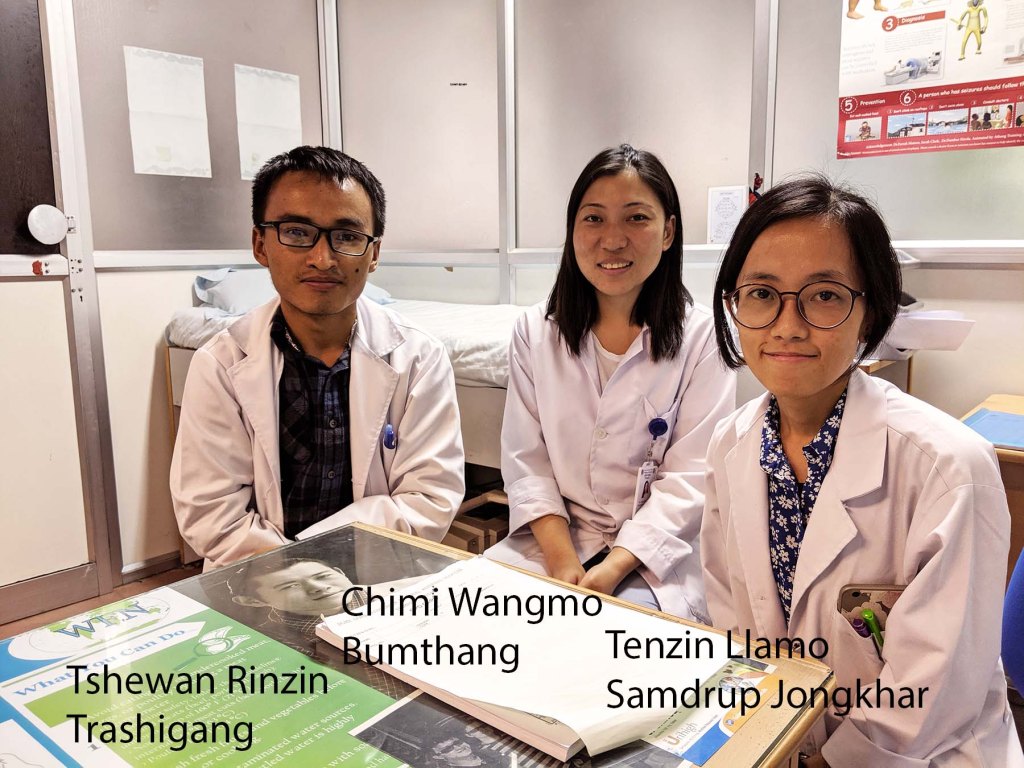

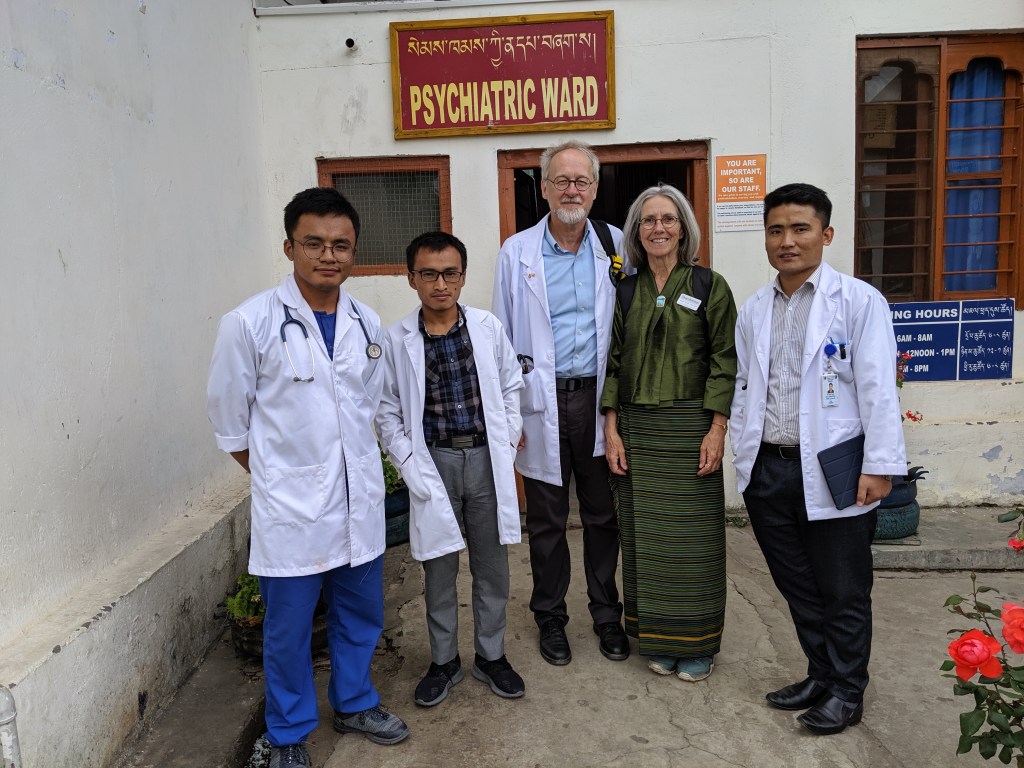

Back to Dr. Steve. One of my most enjoyable tasks here in Bhutan is working with the interns, modeling interviewing skills, reviewing differential diagnoses and treatment planning, critiquing their clinical write-ups and, maybe even more so, learning about them, their backgrounds, the course of their education and their aspirations.

Two essential things are guaranteed by the Constitution of Bhutan: free, universal education and free, universal health care. The Interns are where these guarantees intersect. The first ten years of education aren’t too much different in structure than our own, but things change a bit after that. A National Exam is administered at the end of Class 10. Prior to an initiative by the Prime Minister this year, a student’s Class 10 score determined whether they received a scholarship for Class 11 and 12. Now Class 11 and 12 are free for everyone. Things get a little weird after that. Another National Exam is given in Class 12 and that score actually determines your career and the financing of your continued education. Top scorers are told they can be physicians. Although they can choose a profession at a lower classification, family and social pressures make this difficult.

In the US, aspiring physicians must first complete a four-year Bachelor’s degree, more often than not in a science related field. However, in Bhutan, a doctor in the making goes immediately from Class 12 to Medical School. Bhutan doesn’t yet have its own medical school, so students go abroad, more often than not to Sri Lanka, completing a degree in four years. Tuition and expenses are paid by the Bhutanese Government and, in return, the student is required to practice in Bhutan for twelve years. A one year internship in Bhutan follows, the intern rotating through various specialties, including one month in Psychiatry, after which they are turned loose as a General Doctor Medical Officer (GDMO). Not exactly turned loose. Another National Exam is administered, the results this time determining where they are assigned for the following year. This is where I would be getting scared.

Politically, Bhutan has 20 administrative districts called Dzongkas. In each Dzongka there are numerous Gewongs. In most Gewongs there are Basic Health Units, categorized as BHU 1’s and 2’s. GDMO’s are assigned to the BHU’s. Support services at the BHU’s are limited, BHU 1’s having CBC’s as the only available diagnostic test. BHU 2’s have a few more, along with x-rays and ultrsound. Pharmaceutical formularies are severely limited in Bhutan, even at the regional hospitals, but much more so at the BHU’s. They have access to one antidepressant, amitriptyline, one benzodiazepine, valium and no antipsychotics. GDMO’s are out on the front line, doing everything from deliveries to Psychiatry and basic Orthopedics with limited resources, referring when necessary to one of only three Regional Hospitals, or phoning for remote consultation from senior physicians. Maybe I could have handled this right out of internship but, looking back, I think I would have been scared stiff.

Well…so after internship you have a one year obligation to a BHU before you can apply for a Residency. Exams and interviews again. If you qualify, you can attend a Residency in Bhutan, choosing from Medicine, Surgery, Orthopedics, Pediatrics or, most recently Psychiatry, each in relative infancy. Other specialties are completed abroad. Some GDMO’s choose to remain working at the BHU level. For those who do a Residency, another twelve years of obligated practice in Bhutan is added. It is only after residency that you become an MD (still, you are three years younger than a doctor in the US completing residency). By then, you owe 24 years as an employee of Ministry of Health. There are no private practice physicians. Retirement is then mandatory at age 60.

Caveat: All of the above is what I have learned from the Interns and not confirmed by independent sources.

So… I work hard to tailor what I model and teach the Interns in a way to best prepare them to be out on their own in a BHU. With only two overwhelmed Psychiatrists, along with one first and one second year Psychiatry resident, in all of Bhutan, my one-on-one time with these brave doctors in the making is highly valued and much appreciated. And, it’s a wonderful and rewarding experience for me.

All from Tashigang, off now to Mongar Regional Hospital for the remainder of Internship

This is not a reply, but happy birthday wishes to my favorite sister, Margaret. I don’t know which day you will celebrate in your time zone, but from local time here on 9/23 “HAPPY BIRTHDAY!”

LW

LikeLike