Tango University of Buddhist Studies

‘Tango Monastery, built in 1688, perches on the edge of a thickly forested hill at the northern end of the Thimphu Valley. It looks like a fortress of the gods, soaring towards the skies with its great white semicircular wall gleaming amidst the lush greenery of the trees surrounding it. Enormous windows, framed in intricately carved and painted wood, break the starkness of the outer facade, which encloses a large stone-flagged courtyard. Covered arcades surround the courtyard, their walls painted with beautiful frescoes depicting deities, great saints and lamas. A short but steep flight of stairs leads from the courtyard into the temples and the monks’ dormitories.”

We reached the trail to the monastery after a 40 minute, somewhat hair-raising as usual, drive north from Thimphu.

We were unable to visit the main building of the monastery as it is in the process of restoration. Constructed in 1688, it clearly needs it.

The arrow shot by the Divine Madman Druka Kinley which he followed from Tibet to Chimi is said to be interred inside a Buddha image in the Tango Monastery.

The Himalayan Cypress is the National Tree of Bhutan. It is considered sacred and held in great reverence.

A most unusual campus. The last bit of the hike was definitely vertiginous, too much so to let go my grip and take a photo. I most definitely would not want to return to this campus intoxicated after a night out. But it was definitely worth our pushing through to the top.

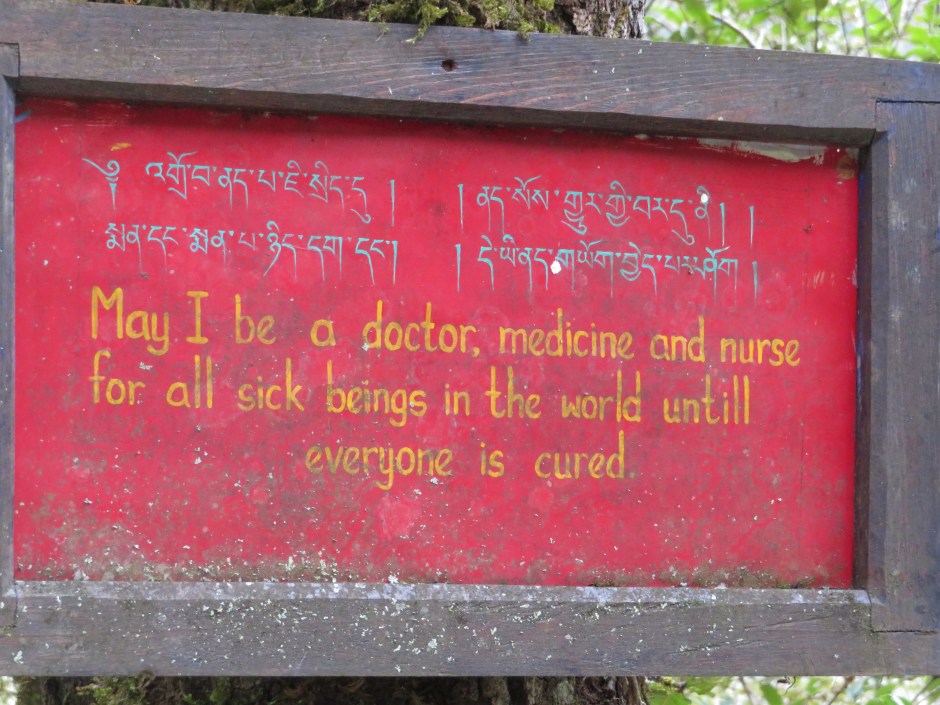

“Young monks in their red robes can always be seen milling around, for Tango is now Bhutan’s main Buddhist Institute, with 200 monks studying there. The hill on which Tango stands is surrounded by little meditation huts, and some of the senior students choose to go into solitary retreat here, traditionally for three years, three months and three days. During this time, the only person they see is their monk-tutor, who brings them food and keeps an eye on their health and welfare. It has to be said that only few are considered emotionally and mentally strong enough to be allowed to go into this long retreat–for it must be a hard thing to commune with one’s innermost self for so long, without any other human contact.”

Tango is the residence of Gyalse Rinpoche the reincarnation of Gyalse Tenzin Rabgye, the builder of both Tango and Taktsang monasteries. There is a fascinating account of his recognition as the reincarnation posted below, taken from Treasures of the Thunder Dragon: A Portrait of Bhutan by Her Majesty Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck, Queen Mother of Bhutan, as are the quoted descriptions above.

“This second story, unlike my personal experience, is not open to multiple interpretations. It is about the discovery in 1998 of a little boy who, after meeting a series of stringent criteria and tests, has been officially recognized as the reincarnation of Desi Tenzin Rabgye, who was the civil ruler of Bhutan from 1680 to 1694. Desi Tenzin Rabgye is a towering figure in Bhutanese history, whom we revere for his radiant spirituality, his strong and enlightened leadership and his brilliant administrative abilities. During his fourteen year reign Bhutan enjoyed peace and tremendous progress. Among his many achievements were the building of the Taktsang Monastery in Paro and the rebuilding of Tango Monastery in its present magnificent form in the Thimphu Valley. Both are among the most hallowed sites in the Himalayan Buddhist World.

In 1998, we were at Kanglung in the Tashigang district in eastern Bhutan for National Day. As is usual on this occasion, the King first addresses a large public gathering, after which he and his family serve lunch to all the people there. This time, during the speech, I noticed a tiny monk sitting on the podium, and wondered who he was. He was very composed and well behaved for his age, which seemed to be not more than four years. After serving lunch to everyone, we headed towards the bamboo enclosure where we were to have lunch, when I saw the little monk still sitting on the podium, all alone. I took him by the hand and brought him to our enclosure, where the King was sitting in a folding chair. The little one let go of my hand and walked straight up to the King. Reaching up to the armrest of the chair he announced: ‘I have something to tell you.’ ‘I’m listening,’ replied the King.

‘We have met before. You were very old, you had a long beard then, and I was very young,’ the child declared. Amused, the King let the little monk continue.

‘I built Taktsang on your orders,’ he said, and added calmly, ‘and now I want to go to Tango.’

‘And why do you want to go to Tango?’ asked the King..

‘I’ve left my things there,’ he replied. ‘And besides, I have to meet my Norbu and my Ugay.’ (We later learnt that these were the names of Desi Tenzin Rabgyes’s monk-attendant and close companion.)

‘So you have been to Tango already?’ asked the King.

‘Yes—a long time ago. It was I who built Tango.’

All of us in bamboo enclosure had gathered around to hear this extraordinary conversation between the King and the little monk. He was just four years old. And, curiously, he spoke in Dzongkha, the language of western Bhutan, and not in his mother tongue Sharchopkha, which is spoken in eastern Bhutan.

‘What are your parents’ names?’ the King asked.

‘Tsewang Tenzin and Damche Tensin,’ he replied. (These were, we later found out, not his parents’ names, but those of Desi Tenzin Rabgye’s parents.)

Could the little monk have been tutored and made to memorize all these details? Yet he answered these and many other questions, which he could not possibly have anticipated, so spontaneously and simply. Soon word spread of this unusual little monk who spoke and acted like an old man. Already, at this young age, he had cataracts in his eyes and very poor vision. So did Desi Tenzin Rabgye, who was practically blind towards the end of his life.

The little monk was born in a humble family in Kanglung. One day the Lam Neten (head abbot) of Tashingang district came to Kanglung for a religious ceremony. The little monk, then just two years old told his mother how sad he was that the abbot did not recognize him, as they had been close associates. The child then asserted that the abbot had been his scribe and they had been very fond of each other. Stories began to circulate about many curious things the child had said and done, and all the details he seemed to know about Desi Tenzin Rabgye, as well as all those who had been close to him.

These reports came to the notice of the Seventieth (and present) Chief Abbot of Bhutan, Je Khenpo Trulku Jigme Choeda. Soon after the little monk’s meeting with the King, the Chief Abbot decided to find out more about the child. He sent one of the four principal monks in the Central Monk Body to examine the child. This senior monk was the Master of Dialectics, the Tsennyid Lopon—a fitting choice, as it was Desi Tenzin Rabgye who had established the discipline of dialectics (or philosophical debate) in the monastic body of Bhutan. From the moment the little monk met the Master of Dialectics, he refused to let him out of his sight—he was worried the Lopon would return to Thimphu and leave him behind, for he had set his heart on going to live in Tango Monastery. The little monk spent the night at the guest house in Tashigang with the Master of Dialectics, who was so impressed by his extraordinary intelligence, and the quiet aplomb with which he conducted himself, that he decided to take him to Punakha Dzong the next day, so that the Chief Abbot himself could meet the child. When they got into the car the next morning, his mother and sisters wept, but the four-year-old was completely fearless and composed as he left with a set of strangers, unaccompanied by a single person he knew.

It was a long journey to Punakha, with an overnight stop in Bumthang, but fortunately the child slept most of the way, only waking up when they had nearly reached Punakha, to ask: ‘Have you a white scarf with the eight auspicious signs on it that I must offer to the Je Khenpo?’ Everyone in the car was amazed that though he had never traveled this far before, he knew when they were approaching Punakha, and also precisely the type of scarf that etiquette demanded he offer the Chief Abbot. Since they arrived at Punakha Dzong late in the evening, the Lopon took the child to his room to rest. But he immediately walked up to mural on the wall, pointed to a building painted there and identified it correctly: ‘This is Humrey Dzong.’ The Tsennyid Lopon was taken aback—how did the child know? Humrey Dzong had been an important Dzong in the seventeenth century, but not a trace of it now remained.

The next morning, 25 January 1999, the little monk met the Chief Abbot. He greeted him observing all the elaborate rules of etiquette that religious protocol demanded, and then watched the Sachoy Ritual which takes place on that day every year. Two top district officials were also there for the occasion, and the child observed that their sword scabbards were exposed. ‘Cover them!’ he instructed, following the rule that prevailed in the seventeenth century, but which no one observed in the twentieth century.

Having spent seven days at the Punakha Dzong, during which he completely won over the heart of the Chief Abbot, the child traveled to Thimphu on the full moon day of the twelfth Bhutanese month—a particularly auspicious day. En route, he was asked if he had ever traveled this route before. ‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘but the last time I came on horseback, otherwise I would not have felt so car-sick on this journey.

While preparations were being made for the little monk to go to Tango, he stayed in my house for nine days. He applied monastic rules to my house, reminding me not to let other women and children into my house after dark. One day the Je Khenpo came to my house for an informal visit and , as I was about to lead him into the sitting room, the little monk suggested that it would be better to take him to the temple first. While we sat there, Zepon Wangchuck unexpectedly came in. Zepon Wangchuck, a former monk, was in charge of rebuilding Taktsang Monastery which had been destroyed in a fire in 1998. The little monk had never seen him before and did not know his name. Yet now he turned to him and said, ‘Make sure you do a good job of rebuilding Taktsang. If you do it well I will give you a gift. And if not…’ He gestured with his little hands to make it clear he would give Zepo Wangchuck a beating!

One day, soon after his arrival in Thimphu, my younger sister showed him a picture of Tango Monastery and asked him if he recognized it. ‘Yes of course’ he retorted, ‘but I don’t see Dzonkha in this picture.’ At that time, none of us knew that Dzonkha was the name of the place above Tango where Desi Tenzin Rabgye used to meditate.

On 20 March 1999, the little monk, whom I shall henceforth refer to as Desi, was carried in a palanquin procession to Tango. All along the way people lined the route to pay homage to him. On reaching Tango, he prostrated before the altar in the main temple, and was then ceremonially as the reincarnation of Desi Tenzin Rabgye.

On 28 April 2005, Taktsang Monastery, the most sacred site in the whole of Bhutan, which had been destroyed in a fire and painstakingly rebuilt over seven years, was consecrated anew. The ceremony was conducted by the little Desi, the young reincarnation of the one who had originally built this monastery three centuries earlier. His presence on that momentous occasion seemed to have been ordained by the Gods.”

Reconstructed from 1998 to 2005